A DC motor is a direct current motor that takes DC electricity and turns it into shaft rotation. Simple statement. Surprisingly many ways to screw it up.

Table of Contents

You feed it from:

- A DC power supply

- A DC drive that rectifies AC

- A battery pack (forklifts, AGVs, EVs, tools)

It gives you:

- Torque on the shaft

- Speed in RPM you can usually control pretty nicely

You’ll see:

- Brushed DC motor

- Brushless DC motor (BLDC)

- Permanent magnet DC motor (PMDC)

- Shunt-wound, series-wound, compound-wound DC motors

And yeah, I still get the question, “Is a DC motor AC or DC?”

Answer: DC. Always DC. The drive might take AC in, but the motor itself is a DC machine.

How does a DC motor work?

Strip it down to the physics that actually matters to you.

The principle of a DC motor:

Put current through a conductor in a magnetic field → Lorentz force pushes it → arrange many of these around a rotor → you get continuous torque.

If you like rules:

- Fleming’s left-hand rule:

- First finger: magnetic field (N to S)

- Second finger: current

- Thumb: motion

Basic Concept:

- Stator creates a magnetic field (field winding or permanent magnets).

- Armature (rotor) has windings carrying current.

- Field + armature current = torque.

- Commutation (mechanical or electronic) keeps the torque direction rotating with the shaft instead of jerking back and forth.

In a brushed DC motor:

- Commutator + brushes flip the current at the right time.

In a brushless DC motor (BLDC):

- The electronics do the switching, like a little 3‑phase inverter.

That’s it. Current and magnetics. Not magic.

I had an apprentice in Detroit who tried to “troubleshoot” a DC motor by ohming everything and declaring it bad because it had low resistance. Yeah, armature resistance in tenths of an ohm is normal. If you don’t understand the basic principle, your meter lies to you.

Construction and main parts

If you can name these parts, you can hold your own in most DC motor talks.

Stator

Stationary outer part.

Contains:

- Field magnets:

- Permanent magnets (PMDC, BLDC rotor is opposite though)

- Or field windings on iron poles (shunt, series, compound)

- Frame / housing

- NEMA or IEC frame sizes in industrial motors

Job: provide a consistent magnetic field.

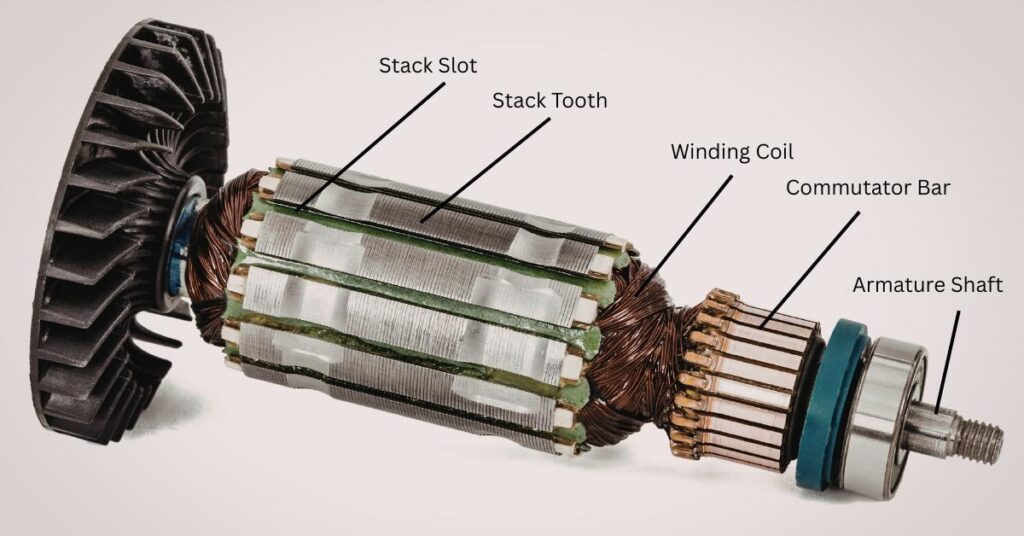

Rotor / armature

Spinning part, on the shaft.

Includes:

- Armature core – laminated steel stack with slots

- Armature winding – copper conductors in those slots

- Commutator – segmented copper ring connected to windings (brushed only)

Job: carry current in the field and convert electrical power to mechanical torque.

On a teardown in a Texas oil & gas skid, we pulled an armature that looked like a barbecue briquette. Field fuse had blown, motor ran weak-field, oversped, current shot through the roof, and the armature insulation gave up. That rotor became a very expensive paperweight.

Brushes (brushed DC)

- Carbon/graphite blocks with springs pushing them against the commutator

- Carry current from your external circuits into the spinning armature

You care about:

- Length vs minimum spec

- Chipping, glazing, burning

- Brush pressure and alignment

Bad brushes = arcing, noise, commutator wear, eventually a call to someone like me at 2 a.m.

Bearings

Same story as AC motors:

- Ball or roller bearings

- Need proper lubrication

- Hate contamination, misalignment, and overheating

A “noisy DC motor” is often just a shot bearing, not some exotic commutation issue.

Extras

- Terminal box: armature terminals (A1, A2), field (F1, F2), maybe tach/encoder leads.

- Cooling: shaft-mounted fan or external blower.

- Feedback (on controlled drives): tach generator, encoder, Hall sensors.

Anyway, if a motor is open and you can’t point to stator, rotor/armature, brushes, commutator, and field magnets/windings, don’t start writing it up as “failed.”

Types of DC motors (brushed, brushless, shunt, series, compound)

This is where most people mix things up, so slow down here for a minute.

Big split: brushed vs brushless DC motor

Brushed DC motor

- Has commutator + brushes

- Armature windings are on the rotor

- Stator has magnets or field windings

- Needs periodic maintenance

Brushless DC motor (BLDC)

- Permanent magnets on rotor

- Windings in stator

- No brushes; commutation handled by electronics

- Runs from DC (battery or DC bus), drive synthesizes 3‑phase-like AC

You see BLDC in:

- CNC axes and spindles

- Robotics, drones, AGVs

- EV traction (often PMSM/BLDC cousins)

- High‑efficiency fans and blowers

Good BLDC systems hit around 80–90% efficiency and pack a lot of power density into a small frame.

Brushed DC motor types

Now the wound-field types and PMDC.

Permanent magnet DC motor (PMDC)

- Stator = permanent magnets

- Rotor = armature winding + commutator

- Flux is roughly constant

Used in:

- Automotive (window lifts, wipers, seat motors)

- Small conveyors, feeders

- Power tools

- Battery-powered gear

Speed behavior (simplified):

Speed ∝ (Voltage − Ia × Ra)

So if you drop more volts, you speed it up, and the Ia × Ra voltage drop at load drags it down a bit.

Shunt-wound DC motor

- Field winding in parallel with armature

- Field current almost constant for given field voltage

Used on:

- Older machine tools

- Fans/blowers needing decent speed hold

- Some legacy conveyors and process lines

Characteristics:

- Good speed regulation

- Medium starting torque

- Speed control via:

- Armature voltage (0–base speed)

- Field weakening (above base speed)

Wait, actually on some older shunt-wound setups with weak field supplies, speed regulation goes to hell under low voltage, but for most decent industrial drives, they behave like people expect: pretty steady.

Series-wound DC motor

- Field winding in series with armature

- Field current = armature current

Very common in:

- Old traction drives

- Cranes, hoists, winches

- Some heavy-duty pumps, compressors

Characteristics:

- Huge starting torque

- Speed skyrockets if you lose load

- This kills motors and sometimes people.

Ever wonder why your series motor screams on no-load? Load drops → armature current drops → field weakens → it tries to keep torque by spinning faster, and faster, until something fails. I saw a test stand near Cleveland where a series motor was run uncoupled “just to check direction.” It reached a pitch that made everyone dive for the disconnect.

Compound-wound DC motor

Combination of shunt and series fields.

- Cumulative compound:

- Series field aids shunt field

- Good for high starting torque and better speed regulation than pure series

- Differential compound:

- Series opposes shunt (ugly behavior, rare in modern stuff)

Used in:

- Elevators

- Press drives

- Some rolling and processing lines

You pick compound when you want a compromise: solid starting torque without crazy overspeed, decent regulation but more grunt than shunt.

Quick comparison table

| Type | Field source | Key trait | Typical use |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMDC | Permanent magnets | Simple, compact | Auto, tools, small conveyors |

| Shunt-wound | Shunt field winding | Good speed regulation | Fans, blowers, machine tools |

| Series-wound | Series field winding | Very high starting torque | Hoists, cranes, traction |

| Compound-wound | Shunt + series | Torque + fair regulation | Elevators, presses |

| BLDC | Electronic + PM rotor | High efficiency, no brushes | CNC, EVs, robotics, HVAC |

Back EMF and why it decides if your motor lives or dies

This is the piece most “just swap it” guys ignore.

When the armature rotates in the field, it generates a voltage opposite the applied DC. That’s back EMF (Eb).

Relationship:

- Eb ≈ k × Φ × ω

- (Φ = flux, ω = speed)

- Armature current:

- Ia = (V − Eb) / Ra

So:

- At standstill:

- ω ≈ 0 → Eb ≈ 0

- Ia ≈ V / Ra → huge inrush, limited only by resistance + current limit of drive

- At running speed:

- Eb almost equals supply (minus some margin)

- Ia small, just enough for torque load

- At increased load:

- Speed drops a bit

- Eb drops

- Ia rises

- Torque increases

I lost half a shift in a Michigan stamping plant because a tech thought, “If I bump the current limits up, it’ll stop tripping.” Back EMF wasn’t building yet at startup, motor was pulling brutal current into a stalled load, drive finally blew an SCR. Downtime bill stayed on the wall for a year as a reminder.

Back EMF is why:

- You never hardwire a DC motor across a big DC bus with no current limiting.

- Stalled DC motors cook crazy fast.

- Drives ramp and limit current instead of slamming full power.

Speed control and torque characteristics (how DC really behaves)

Torque vs current

For a DC motor with constant flux (Φ):

Torque ∝ Ia

So:

- Double armature current → roughly double torque (up to saturation, thermal limits).

- Current limit on the drive = torque limit.

Speed vs torque for each type

Shunt or PMDC:

- Flux basically constant.

- Speed only drops a bit with load (due to Ia × Ra).

- Nice for constant-speed applications.

Series:

- Torque goes through the roof at low speed.

- Speed rises as load drops.

- Dangerous if unloaded.

Compound:

- Tunable middle ground.

BLDC:

- Torque set by current reference in drive.

- Speed set by applied electrical frequency and voltage.

- Torque curve is flat up to base speed, then you hit constant power (like field-weakening region in DC).

Ever see a DC motor that “won’t hold speed” but the drive is fine? Check:

- Armature resistance (overheated windings raise it).

- Supply sag on the DC bus.

- Field current dropping because someone “adjusted” the wrong pot.

How much electricity does a DC motor use?

This is the part management asks you about when they hear “energy efficiency” and “BLDC” in the same sentence.

Basic formula:

P (watts) = V × I

For a DC motor:

- Input electrical power ≈ V_armature × I_armature (+ field power on wound-field units)

- Mechanical output power = Torque × speed

If you want HP:

HP ≈ (Torque (lb-ft) × RPM) / 5252

If you know efficiency (η):

Input kW ≈ Output kW / η

Typical efficiencies:

- Old brushed DC:

- 70–85% for smaller units

- 85–90% for bigger, well-designed ones

- BLDC / PM synchronous:

- ~80–90%+ when sized right

Example:

- 5 HP DC motor (≈3.7 kW output)

- 85% efficient

- Input ≈ 3.7 / 0.85 ≈ 4.35 kW

Run:

- 8 hours/day → 34.8 kWh/day

- At $0.10/kWh → about $3.50/day

I worked a CNC shop in California where we swapped two old brushed spindles for modern BLDC/servo systems. Same cutting performance, but the line’s power monitoring showed a few kW less draw per machine under typical load. That, plus less downtime on brushes, paid the upgrade off faster than I expected.

DC vs AC motors (why you pick one over the other now)

People ask: What’s the difference between AC and DC motors, and why would I use DC?

Short version:

- DC motor:

- Better low-speed torque and speed control (especially older tech).

- Needs more maintenance (if brushed).

- Great for battery-powered and legacy systems.

- AC motor (induction/PMSM) with VFD:

- Now does 90% of what DC used to own.

- Less maintenance.

- Cheaper for many HP ranges.

| Aspect | DC Motor | AC Motor (with VFD) |

|---|---|---|

| Supply | DC (or rectified DC from AC) | AC (3‑phase, then rectified inside VFD) |

| Commutation | Mechanical (brushed) or electronic (BLDC) | Electronic in VFD, no brushes |

| Maintenance | Higher on brushed units | Lower (mostly bearings) |

| Speed control | Excellent | Excellent with modern VFD |

| Hazardous/Class areas | Brush arcing is a problem | Induction easier to certify and use |

| Preferred today | Legacy drives, BLDC/servo, battery systems | Pumps, fans, conveyors, most new plant installs |

I’ve told more than one engineer: “If you’re starting from scratch and not on a battery, AC + VFD is usually the right answer. But if you’ve already got a DC line with millions tied to its throughput, you treat those DC motors like gold and maintain them, you don’t rush to ‘modernize’ mid-peak season.”

Advantages and disadvantages of DC motors

Advantages

- Great variable speed control with simple concepts: armature volts + field current.

- High starting torque, especially in series/compound motors.

- PMDC and BLDC motors:

- High power density.

- Good efficiency.

- Strong low-speed performance.

Disadvantages

- Brushed DC:

- Brushes + commutator = wear items.

- Arcing, carbon dust, potential UL/safety headaches in hazardous or clean environments.

- Drives:

- Old SCR DC drives are bulky, less efficient, and a bit ugly compared to compact VFDs.

- Higher installed/maintenance cost vs standard AC + VFD in many HP ranges.

- Commutator limits maximum safe RPM mechanically.

I once had a plant manager ask why we couldn’t just “forget the brush PMs” on a DC hoist and run it till failure. He changed his mind after an unplanned failure locked a 10‑ton coil mid-lift and OSHA got interested. Planned brush changes are a lot cheaper than safety investigations.

Real-world applications of DC motors

You’ll actually run into these more than you think.

In plants

- Steel rolling mills – big, old DC armatures driving stands.

- Paper/film/foil lines – legacy DC drives on each section.

- Elevators and hoists – DC traction motors on older systems.

- Cranes, winches – series or compound DC for high torque.

- Conveyors and feeders – lots of 90 VDC PM motors in older US plants.

Automation and CNC

- CNC machines:

- Old axes: brushed DC servos with tach feedback.

- Newer: BLDC/AC servos, but concept similar.

- Robotics / actuators:

- PMDC and BLDC used all over for joints, grippers, linear actuators.

- Adjustable speed drives:

- Legacy Allen-Bradley, Siemens DC drives still earning their keep.

On a line in Ohio, I saw a mishmash: three PowerFlex VFD-driven AC motors, then right next to them, two ancient 500 VDC shunt motors still pulling a web. Guess which ones had the least unplanned downtime that year? The DCs. Because the old-timer there respected them and did his brush and commutator maintenance like clockwork.

Everyday / mobile

- Power tools – drills, saws, impacts (brushed or BLDC).

- Electric vehicles – traction motors (older ones DC, lots of modern ones PM synchronous/BLDC style).

- Battery devices – toys, drones, e-bikes.

- Automotive – fans, pumps, window motors, seat adjusters.

Maintenance that actually saves your DC motor

If you ignore this section, you’ll be buying motors and drives instead of greasing bearings.

Brush replacement and wear

- Check on a real PM interval (every few hundred hours for tough duty, or per OEM).

- Look for:

- Length below min

- Cracks, chips

- Glazed or burned faces

- Use correct brush grade. Wrong carbon grade → hot commutator and poor life.

I had a Detroit shop “save money” buying generic brushes. Six months later we were sending armatures out for turning and undercutting twice as often. Their savings went straight out the window.

Commutator cleaning and care

- Clean dust out with dry air (not 150 psi right into the windings, you know).

- Use proper commutator stones, not sandpaper and not files.

- Watch for:

- Deep grooves

- Raised mica

- Pitting/burn marks

Once the commutator goes out-of-round, brush bounce and sparking explode.

Bearings and armature balance

- Lube right; don’t overpack or mix greases.

- Check vibration and noise regularly.

- After a rewind, make sure the shop did a good dynamic balance on the armature.

An unbalanced armature beats the life out of bearings and then everyone blames “electrical.”

Overheating prevention

- Size the motor right – running at 120% load all day cooks it.

- Verify field current is correct on wound-field motors.

- Keep cooling paths open.

- Use IR gun on housing – anything climbing way above nameplate temp rise should make you nervous.

I saw a Michigan web line motor where the cooling fan intake was half-blocked by shrink-wrap and cardboard fluff. They were investigating “drive faults.” Drive was fine; the motor was baking itself.

Spark and arcing checks

- Normal: tiny, uniform brush sparking under some loads.

- Bad:

- Heavy blue/white arcs

- Uneven sparking around the commutator

- Loud buzzing, smell of burning

If you see that:

- Check brush seating and pressure.

- Inspect commutator.

- Check for loose armature or field leads.

I once found a field lead on a DC blower hanging by two strands. Every time load shifted, it sparked like crazy. Tightened, cleaned, re-torqued all lugs … problem gone.

Quick history, just for context

You don’t need this to fix a DC motor, but it explains why we still see them.

- Michael Faraday (1820s) shows that current + magnetic field = motion.

- Thomas Davenport builds early practical DC motors in the 1830s.

- Late 1800s–1900s: DC motors drive early factories, streetcars, mills.

- Mid to late 1900s:

- Big DC drives rule for variable speed in heavy industry.

- AC induction + VFD eventually take over most new installs.

- 2000s:

- BLDC and high-efficiency PM motors show up everywhere: EVs, robotics, HVAC.

So those old DC motors in your plant aren’t “ancient junk.” They’re survivors from an era when DC was the only serious option for variable speed. Treat them right and they’ll outlast that new laptop in your maintenance office by decades.

If you’ve got a DC motor right now that’s:

- Overspeeding on no-load,

- Tripping on overcurrent at startup,

- Chewing brushes every few weeks,

Tell me the symptoms and what drive you’re running (Allen-Bradley, Siemens, etc.), and I’ll tell you where I’d put the meter first.

Learn more about Air Circuit Breakers in our complete guideCommon FAQ for DC Motor

How does a DC motor work?

Put current through conductors in a magnetic field → Lorentz force creates push → arrange them on a rotor with commutation (brushes or electronics) to keep the push going in circles. That’s torque. Back EMF builds as it spins to limit current. No magic, just current, magnets, and smart switching.

What are the common types of DC motors?

Brushed (PMDC, shunt-wound, series-wound, compound-wound) vs. brushless (BLDC). PMDC for simple stuff like tools, shunt for steady speed, series for massive startup torque (but dangerous at no load;), compound for a balance, BLDC for modern, high-efficiency jobs like CNC or EVs.

What is the principle of a DC motor?

Lorentz force says; current-carrying conductor in a magnetic field gets pushed perpendicular. Fleming’s left-hand rule tells direction (first finger field, second current, thumb motion). Commutation flips current so the push always rotates the shaft instead of rocking back and forth.

What is the difference between AC and DC motor?

DC runs on steady current (direct from battery or rectified), easier speed control in legacy setups, but brushed ones need maintenance. AC (induction/PMSM) uses alternating current, VFDs now handle speed/torque great, less maintenance, cheaper for most new plants. DC wins in battery systems or old heavy-torque lines.

Why is a DC motor used?

High starting torque (especially series/compound), smooth variable speed control (armature voltage + field tweaks), works great on batteries/low-voltage DC buses. Still hangs on in legacy plants, EVs traction (BLDC style), tools, robotics, and where AC retrofit costs more than keeping DC running.

How to control speed of DC motor?

Armature voltage variation (main way for constant torque), field weakening (above base speed, but torque drops), PWM for small/PMDC motors (duty cycle chops voltage efficiently). Drives handle current limiting and ramps to avoid cooking it on startup.

What are the basic parts of a DC motor?

Stator consist of field magnets or windings + frame, While rotor/armature consist of core, windings, commutator in brushed, brushes (carbon blocks on commutator), bearings, terminal box, cooling fan. BLDC flips it: magnets on rotor, windings on stator, no brushes, electronics do the switching.

Is the DC motor AC or DC?

It’s DC Always. The motor windings see direct current. Drives might take AC in and rectify it, or BLDC drives create phased waveforms internally, but the machine is classified as DC because it runs on unidirectional current.