Introduction – Why Arc Fault Scare the Hell Out of Me After 25 Years

The first time I saw an arc fault turn into a “how is that place still standing?” kind of fire, it wasn’t some dramatic lightning strike or a forklift spearing a conduit. It was boring. A normal building. Normal day. The kind of job where you expect to swap a bad receptacle, tighten a few lugs, and be home in time to complain about your knees.

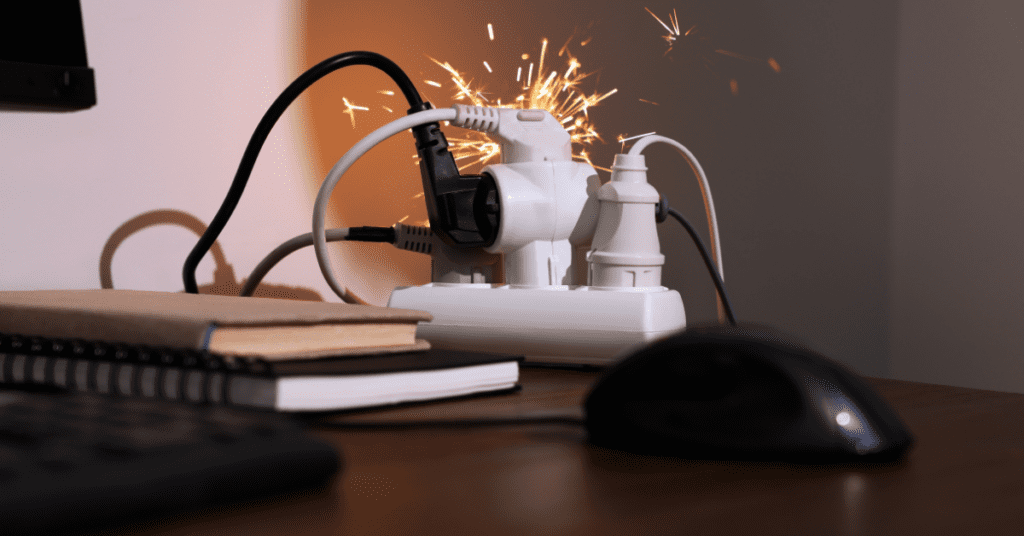

We got called in after hours because the place had that smell. You know the one, hot plastic, stale smoke, and regret. The maintenance guy swore nothing happened. “Breaker never tripped,” he says. That’s the line I’ve heard a hundred times. We open up a junction box above a drop ceiling and find it: a wirenut that was barely hanging on, blackened conductors, and insulation cooked back like a cheap hot dog split open on a grill. The ceiling tile above it had a perfect brown halo. Another hour and that whole wing would’ve been on the news.

That’s why arc faults scare me. Not because they’re mysterious. They’re not. They scare me because they’re sneaky, they don’t behave like a dead short, and they can sit there making dangerous arcing for a long time while your standard breaker shrugs and goes back to sleep.

NFPA and CPSC have been beating the drum for years about preventable electrical fires, bad terminations, damaged wiring, cords pinched under furniture, “temporary” extension cords that become permanent. The exact numbers change depending on which report and which year you read, but the theme never does: a big chunk of residential fires trace back to wiring faults and arcing fault behavior that regular overcurrent protection doesn’t always catch fast enough. And if you think this is a “house problem,” you haven’t spent much time around industrial control panels that vibrate, heat-soak, collect dust, and get “modified” at 2 a.m. by whoever drew the short straw.

Here’s the part people miss: arc-fault protection isn’t about stopping every electrical problem. It’s about fire hazard mitigation. It’s about de-energize the circuit fast when the current waveform screams “this is an electrical arc, not a normal load.”

That matters in homes. Bedrooms were the early battlefield, lamp cords, space heaters, beat-up vacuum cords, kids with bunk beds crushing cords behind headboards. Then living areas. Then more areas. Kitchens get weird because of appliance noise and shared circuits, but the direction of travel has been clear for a long time: more AFCI coverage.

It matters even more in factories than most folks want to admit. “We’ve got three-phase, we’ve got fuses, we’ve got motor protection.” Yeah. And I’ve also seen a loose neutral in a 120 V control circuit make a PLC cabinet smell like toast while the main breaker sits there happy as a clam. I’ve seen a VFD output lead rub on a sharp gland plate until it started tracking to ground through the insulation. I’ve watched a door-mounted disconnect get installed with lugs that were “tight enough” until the machine started shaking like it was auditioning for a paint mixer.

An arc fault doesn’t need a lot of current to make a lot of heat in the wrong place. That’s the whole ugly point. When copper is barely touching copper, that contact point becomes a heater. When it separates and re-connects, you get ionization and a plasma arc. The temperature in the arc can get north of 10,000°F in a blink. That’s hotter than the surface of the sun? No. Don’t get cute. But it’s hot enough to wreck insulation, carbonize surfaces, and start a fire in material that has no business being part of your circuit.

And yeah, I’m Jack Harlan. I’ve been doing this 25 years. I’ve taught apprentices who thought torque specs were a suggestion, and I’ve cleaned up after panels wired by people who apparently hate humanity. This post is the straight story: what an arc fault is, why it burns down buildings and machines, how an arc fault circuit interrupter (AFCI) actually works, what the National Electrical Code (NEC) is asking for under NEC Article 210.12, and how this all plays out in industrial control panels where downtime costs real money.

If you’re looking for fluffy marketing about “peace of mind,” you’re in the wrong place. If you want to stop electrical fires and stop getting surprised by nuisance tripping, keep reading.

Breaking Down What an Arc Fault Actually Is

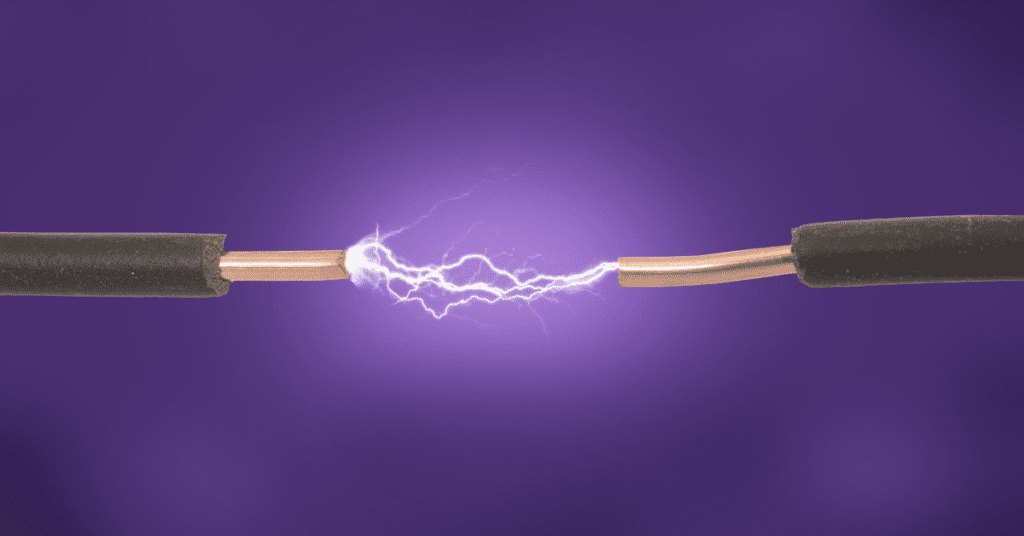

An arc fault is unintentional arcing, current jumping through air (or through a carbonized path) instead of traveling through a solid, low-resistance conductor path like it’s supposed to. It’s not a normal load. It’s not a clean bolted short. It’s a messy, noisy electrical arc that can sputter and spit.

Two main flavors matter in the real world: series arc and parallel arc.

A series arc happens in series with the load. Think “loose connection.” A backstabbed receptacle that’s been warming and cooling for years. A terminal screw that wasn’t torqued. A crimp that was done with pliers because the right tool was “somewhere.” The conductor is still technically connected, so the current might not spike high enough to trip a standard breaker. But the connection is resistive and unstable. As the contact area changes, vibration, thermal expansion, corrosion, you get micro-separations, and the current arcs across the tiny gap.

A parallel arc is line-to-neutral, line-to-ground, or line-to-line arcing. That’s damaged insulation, a staple through a cable, a cord cut, a conductor nicked and pushed against a grounded box. Parallel arcs can pull higher current than series arcs, but they still might not look like a clean short. The arc is dynamic. It can self-limit. It can hop. It can extinguish and re-strike 120 times a second on AC. That “chatter” is part of what arc detection algorithms look for.

Let’s talk physics without getting precious about it. When you separate conductors under load, the electric field across the gap can ionize air. Once it ionizes, air stops acting like an insulator and starts acting like a conductor, plasma. That’s the plasma arc. Ionization lowers the resistance of the path, current flows, and you get a tiny blowtorch where no blowtorch should be.

That’s the part that cooks things. The arc column can hit high-intensity heating over 10,000°F locally. The copper doesn’t have to melt for you to have a serious problem; insulation and nearby combustibles ignite way sooner. PVC insulation deforms, cracks, and carbonizes. Once surfaces carbonize, they can become a conductive path. Then you’re not just dealing with an arc in open air; you can get tracking along the insulation, across dust, across moisture, across that nice layer of “panel seasoning” that builds up in industrial cabinets. Ugly.

Now here’s the kicker: regular breakers are designed primarily for overload vs short. Thermal-magnetic breakers trip on sustained overcurrent (thermal) and big instantaneous faults (magnetic). A series arc can sit below the trip curve all day while it makes enough heat at a connection point to start cooking. A parallel arc might spike, then drop, then spike again, never staying high enough long enough to trip a standard breaker quickly.

So arc faults sneak through. That’s not a defect in breakers. That’s them doing what they were designed to do, protect wiring from overcurrent, not detect “weird” current signatures.

AFCI protection exists because waveform monitoring exists. We can analyze the sine wave and look for the fingerprint of arcing: high-frequency components, erratic current steps, non-linear conduction, that telltale “buzz saw” pattern that doesn’t belong in a toaster or a motor.

And before someone pipes up: yes, some arcing is normal. Brushes in certain motors. Switch contacts opening. Relays. Contactors. The difference is duration, location, and pattern. An electrical arc fault is unintentional and persistent enough to create a fire hazard. That’s what we’re hunting.

The Usual Suspects – What Causes These Arcs in Real Life

Most arcing faults I’ve traced didn’t start with some exotic failure. They started with “good enough” work and time.

Frayed cords are classics. Extension cords pinched in doorways. Appliance cords shoved behind a fridge until the copper work-hardens and breaks strand by strand. People running cords under rugs like they’re hiding evidence. In plants, it’s worse, cords dragged across concrete, run over by carts, zip-tied to sharp edges. I’ve opened up portable control boxes where the SO cord jacket looked like it got in a fight with a belt sander.

Damaged wiring inside walls is another one. Residential: hammered Romex, staples driven like the installer was mad at it, nails through cable, drywall screws doing drywall screw things. Commercial/industrial: cable tray edges, poor strain relief, missing bushings, conduit with reamed ends that weren’t reamed at all. If you’ve ever pulled wire through a pipe that had a razor edge and thought “eh, it’ll be fine,” that’s you planting a time bomb.

Loose connections in panels are the champ, though. Loose lugs, loose neutrals, loose grounds. And don’t get me started on neutrals. A loose neutral in the panel can create all kinds of ghost problems that mimic arc behavior, cause overheating wires, and lead to nuisance tripping on AFCIs. I’ve seen neutral bars packed like a sardine can, two conductors under one screw where it’s not listed for it, strands half captured, insulation under the clamp, and the whole thing “tight” because the screwdriver stopped turning.

In industrial machines, vibration is the silent assassin. Motor starters and contactors slamming all day. Conveyors shaking. Presses thumping. Robots moving. Fans humming. Every one of those is a little mechanical stress cycle on terminations. Even a properly torqued screw terminal can loosen over time if the hardware and conductor settle, if the conductor creeps (especially with aluminum, but copper moves too), or if someone didn’t use the right ferrules on fine-strand wire. Those little movements create micro-gaps, and micro-gaps create arcs.

Corrosion gets ignored until it’s too late. Damp plants, washdown areas, coastal facilities, chemical vapor environments, corrosion increases resistance and ruins contact quality. I’ve opened up outdoor disconnects where the copper was green, the steel was orange, and the whole thing looked like it came off the Titanic. Corrosion plus load equals heat. Heat plus insulation equals failure. Failure plus oxygen equals the bad day.

Then you’ve got the “modifications.” The midnight specials. Someone adds an outlet. Someone taps a control transformer. Someone extends a circuit and doesn’t land the ground right. Someone uses the wrong connector. Someone leaves a strand whisker that’s just waiting to bridge. Wiring faults love human beings. We’re creative.

And look, I get it. Production is screaming. The line is down. The supervisor wants it running yesterday. That’s how you end up with a conductor jammed into a terminal that’s too small, or a splice floating in a cabinet with no enclosure, or a door flexing a wire bundle until the insulation wears through.

Most of these aren’t “mystery failures.” They’re maintenance failures. Tighten connections. Protect conductors from abrasion. Use proper strain relief. Replace damaged wiring. Stop pretending temporary fixes are permanent.

How One Tiny Arc Turns Into a Full-Blown Fire

Fire doesn’t need drama. It needs heat, fuel, and oxygen. Arc faults hand-deliver heat.

Step one is usually a small resistive point. A loose screw terminal, a nicked conductor, a corroded splice. Current flows. The resistive point warms. That heat softens insulation and accelerates oxidation. Resistance goes up. Now it warms faster. That’s the runaway.

Step two is intermittent contact. Vibration or thermal cycling opens a microscopic gap. Voltage is still there, so the field ionizes the gap and you get an arc. The arc erodes metal, pitting the conductor and making the contact worse. It also spits molten metal. That molten metal can land on insulation, dust, paper, wood, oily residue, whatever’s nearby.

Step three is carbonization and tracking. Insulation that gets cooked turns into carbon. Carbon conducts. Now you can get a conductive path across what used to be insulating material. The arc becomes easier to sustain. It can crawl along surfaces, especially if there’s moisture or grime. In industrial cabinets, dust plus humidity can become a nice little highway for trouble.

Step four is ignition. Surrounding material hits its ignition temperature. It might smolder first. That’s why you sometimes smell it hours before anything “happens.” Smoldering becomes flame. Now you’ve got a real fire, and your breaker still might not trip because the current isn’t a dead short. It’s just a heater that’s now on fire.

“Why didn’t the GFCI catch it?” Because a GFCI is looking for imbalance between hot and neutral, current leaking to ground. If your arc is line-to-neutral in a cord, the current can be perfectly balanced. The GFCI sits there politely. Standard breakers? Still looking for overcurrent. An arc can sit in that nasty middle zone where it’s dangerous but not high enough to trip fast.

This is where CPSC and NFPA stats matter, not as trivia, but as proof that this isn’t hypothetical. Electrical fire prevention isn’t just “don’t overload circuits.” It’s also “stop arcing faults before they become ignition sources.” That’s why AFCIs exist at all.

Sorting Out the Confusion – Arc Fault vs Ground Fault vs Short vs Overload

You’d be amazed how many techs even good ones mix these up when they’re under pressure.

Overload: too much current for too long. Think motor overloaded, too many space heaters, circuit packed with loads. Conductors heat up along their length. Thermal element in the breaker trips. Usually not an immediate bang; more like “why is this breaker warm?”

Short circuit: low-impedance path between conductors that shouldn’t be connected, like hot to neutral. Current skyrockets. Magnetic trip acts fast. That’s your “pop” and sometimes the flash.

Ground fault: current leaving the intended circuit path and going to ground. That can be hot-to-ground contact, or leakage through a person. GFCI devices trip when the difference between hot and neutral exceeds a small threshold. Great for shock protection. Not designed primarily for fire protection, though it helps in some cases.

Arc fault: unintentional arcing, series or parallel, often with current that’s not high enough or steady enough to trip a standard breaker. Fire problem first. Shock problem sometimes. Equipment damage problem often.

If you want a mental checklist: ask yourself “Is the current too high and steady?” (overload). “Is it insanely high and immediate?” (short). “Is current leaking to ground?” (ground fault). “Is it noisy, intermittent, heat-at-a-point, and smells like burning plastic?” (arc fault). It’s not perfect, but it’ll keep you from chasing the wrong gremlin.

And yes, these can overlap. A parallel arc can become a short. A ground fault can include arcing. Real life doesn’t care about neat categories.

AFCI Breakers – How They Spot Trouble and Shut It Down

An arc fault circuit interrupter isn’t magic. It’s electronics plus a trip mechanism plus a set of rules. The AFCI monitors the current waveform, sine wave analysis in plain English, and looks for patterns that match arcing. It’s waveform monitoring, not “it got hot” monitoring.

Inside the breaker, you’ve got electronic sensing: current transformers, filters, and a processor running an algorithm. It’s hunting high-frequency noise components and the erratic on-off conduction that arcs produce. Normal loads have signatures too, so the AFCI has to ignore stuff like dimmers, motor commutation noise, switching power supplies, and yes, LED drivers. That’s where the quality of the algorithm and the design matters.

UL 1699 is the big standard for AFCIs. It’s not just “does it trip?” It includes test waveforms and setups meant to simulate series arcs and parallel arcs under different conditions. UL basically tortures these devices and checks that they trip when they should and don’t trip when they shouldn’t. In Canada, you’ll see CSA C22.2 NO. 270 come up in the conversation too, depending on the gear and application.

Types you’ll hear about:

Combination-type AFCI: This is the common modern answer for dwelling unit branch circuits. Despite the confusing name, “combination” here refers to the ability to detect both series and parallel arcing (not a combo of AFCI and GFCI). These are the ones NEC 210.12 typically drives you toward.

Branch/feeder AFCI: Older style. More limited arc detection coverage compared to combination-type, especially on series arcs. You’ll still run into them in older installs.

Dual-function AFCI/GFCI: One device, both protections. Handy when code wants both arc-fault protection and ground-fault protection in the same area. Also handy when the panel is full and you don’t want to play device Tetris.

Brands? Look, I’m not married to logos. I’ve installed Leviton, Siemens, Eaton, Schneider Electric, plus the usual big names everyone already argues about. In most cases, if it’s UL-listed gear only and it’s matched to the panel, you’re fine. What I care about is using the correct breaker for the panel (listed for it), landing neutrals correctly, and not mixing shared neutrals like it’s 1987.

Some brands seem a little more tolerant of certain nuisance signatures than others, and some panels play nicer with their “native” breakers. That’s not superstition; it’s the reality of tolerances, bus design, and the arc algorithms. But don’t use that as an excuse to slap in the cheapest thing you found online from a seller named “BestDealz_4U.” Use listed equipment. If the supply chain looks shady, it probably is.

The point of an AFCI is simple: detect arcing behavior and de-energize the circuit fast enough to reduce the chance of ignition. Not eliminate all risk. Reduce it. Big difference.

The NEC Rules – Where You Have to Use AFCIs (and Where You Probably Should Anyway)

NEC Article 210.12 is where the AFCI story lives for dwelling unit branch circuits. The code started with bedrooms years back, then expanded. That expansion wasn’t because someone wanted to sell more breakers. It was because the fire data and field experience showed that arcing faults don’t politely stay in bedrooms.

The exact “where” depends on the NEC edition adopted in your jurisdiction. That’s the part that drives everybody nuts, code compliance headaches where one town is on 2014, the next is on 2017, and the inspector has opinions that predate all of it. In general, the trend has been broader coverage across habitable spaces and many 120 V, 15 and 20 A branch circuits in dwelling units. Kitchens, laundry areas, and similar spaces can involve both AFCI and GFCI requirements, and that’s where dual-function AFCI/GFCI devices show up a lot.

I’m not going to play lawyer with every exception and local amendment here, because the minute I do, some county will have a twist. Read the adopted NEC edition, check local amendments, and coordinate with the AHJ. That’s the grown-up answer.

Now, industrial and commercial: AFCIs aren’t blanket-required the same way in typical industrial control panels. You’re dealing with different articles, different occupancy types, and different equipment listings. But don’t confuse “not mandated everywhere” with “not useful.” Fire hazard mitigation isn’t only a dwelling unit concern. I’ve seen control power transformers feeding long 120 V control runs, receptacles in maintenance areas, and cord-and-plug equipment inside plants that look an awful lot like the conditions AFCIs were designed for.

Inspectors tend to focus on two things: correct application per 210.12 where it applies, and UL-listed gear only. Also, clean neutral/ground separation and correct wiring methods, because an AFCI will expose your sloppy work fast.

Nuisance Tripping – The Bane of Every Electrician’s Existence

AFCIs get blamed for a lot of sins that belong to wiring.

What makes AFCI breakers trip? Sometimes, they trip because there’s an arc fault. Imagine that. But yes, nuisance tripping is real, and it’s usually one of a few things.

Loose neutrals are a big one. A loose neutral in the panel or at a device can create noise and intermittent current paths that look like arcing. I’ve walked into houses where the AFCI “randomly trips,” and the fix was tightening the neutral bar screw that was barely biting. Same in industrial panels, poor neutral terminations on control circuits can create weird voltage behavior and chatter that triggers sensitive electronics.

Shared neutrals and multi-wire branch circuits miswired are another. If you’ve got a multi-wire branch circuit and the neutrals aren’t handled right, or the breakers aren’t tied properly, you can get imbalance and ugly waveforms. Some AFCIs don’t like that, and frankly, they shouldn’t.

Then there’s load-generated noise. Certain LED drivers, cheap power supplies, treadmills, vacuum cleaners, older brushed motors, some of these create signatures that look arc-ish. In industrial controls, motor inrush and contactor chatter can be rough too. A coil that’s undervoltage because of a bad transformer tap or long run can chatter a contactor, creating repeated make/break events. That’s not an arc fault in the wiring, but it’s definitely abnormal and can trip an AFCI depending on the scenario.

How do you hunt it down without losing your mind?

Start simple. Monthly AFCI testing is great, but when it’s tripping unexpectedly you need isolation. Unplug loads. Turn off switches. Divide and conquer. If it trips with nothing plugged in, you’re looking at wiring or devices. If it trips only when a certain load runs, you’ve found a suspect.

Next, check terminations. Yes, all of them. Panel neutral and hot, device screws, splices. Use a torque screwdriver when it matters. Eyeballing wiring for frays or damage isn’t glamorous, but it works. Look for nicked insulation, loose wirenuts, backstabbed devices that should’ve been screw-landed, and cords that have seen better decades.

In industrial settings, look for vibration points. Door harnesses rubbing on sharp edges. Wire duct covers missing and conductors laying across sheet metal. VFD wiring too close to control wiring, causing noise issues that aren’t arc faults but can create strange behavior. Make sure your grounding and shielding practices are solid.

And if you’re stuck? This is where “knowing when to call in a real sparky” saves time. Some problems need an insulation resistance test, thermal imaging, a scope on the line, or just a seasoned set of eyes. There’s no shame in that. The shame is bypassing protection because you’re annoyed.

Keeping AFCIs Alive – Testing and Maintenance That Matters

That little push-to-test button isn’t decoration. Use it.

Monthly AFCI testing is a good habit in homes, and in industrial environments I like tying testing into preventive maintenance schedules. Not because AFCIs fail constantly, they usually don’t, but because nobody remembers they exist until something trips or burns.

When you test, understand what you’re doing: you’re verifying the breaker’s internal trip function, not proving your wiring is perfect. Still valuable. If it won’t trip on test, replace it with the correct listed device for the panel. Don’t get cute.

In dusty plants or harsh environments, keep cabinets sealed, filtered, and properly cooled. Heat is the enemy of electronics. So is conductive dust. Also, don’t ignore routine checks: checking for tight connections, looking for discoloration, sniffing for that “hot” smell, and steering clear of overloaded circuits that cook insulation over time.

If a breaker starts tripping and you’ve ruled out load and wiring, replacement is sometimes the right call. Electronics age. Surges happen. Just don’t replace your way out of a wiring problem.

Arc Faults in the Industrial World – Control Panels, Machines, and Big Money Risks

Here’s where my controls people lean in.

Industrial control panels aren’t wired like houses, but arc faults don’t care about your career path. They care about bad connections and damaged insulation.

Inside a PLC cabinet, you’ve got a mix of AC and DC, high and low voltage, noisy power electronics, and a whole lot of terminations. Terminations are where arc faults are born. A poorly landed wire on a 120 V control transformer secondary can arc. A loose terminal on a DIN rail power supply can arc. A relay base with a fatigued spring contact can arc. A door-mounted pilot light with a pinched conductor can arc every time the door swings.

Then add VFDs. VFD wiring is its own animal. Output leads see high dv/dt, and insulation stress is real. If you route VFD output through tight bends, rub points, or cheap cord grips, you’re asking for insulation damage. Once insulation degrades, a parallel arc to ground can start tracking. Sometimes you’ll see it as nuisance drive faults before you see smoke. Sometimes you’ll see smoke first.

Motor starters and contactors? They arc internally by design when contacts open under load, but that arcing is contained in the device. The problem is when the line/load terminations are loose, or when the contactor is chattering because the coil voltage is unstable. That chattering can hammer the contacts and create external heat at terminations. I’ve seen the plastic around a contactor terminal deform because the screw wasn’t tight and the conductor was carrying near-full load. That’s not “normal wear.” That’s a loose connection turning into a heater.

Machinery that vibrates loose over time is the other big one. Packaging lines, crushers, mixers, stamping presses, anything that shakes. If you don’t use ferrules where appropriate, if you don’t strain-relief properly, if you don’t secure wire bundles so they’re not flexing at the same point every cycle, you will eventually get a conductor break or a loose termination. That’s when series arc behavior shows up.

Now let’s talk downtime and risk. A house fire is tragedy. In a plant, you can lose a machine, a line, inventory, and weeks of production. I’ve seen a small cabinet fire shut down an entire area because smoke contamination forced cleanup and inspections. I’ve seen insurance companies get real interested in maintenance records after an incident. Electrical safety isn’t just “don’t get shocked.” It’s “don’t burn the place down and don’t shut down the business.”

So what’s the industrial equivalent of AFCI protection? Sometimes it is AFCI on 120 V receptacle circuits feeding maintenance outlets, on control power circuits where code and design allow. Sometimes it’s other strategies: better enclosure management, arc-resistant designs, proper conductor protection, insulation monitoring, thermal monitoring, and good old-fashioned workmanship.

But don’t dismiss AFCIs as “residential toys.” In the right place, they’re a solid layer of protection. Especially for those weird intermittent faults that don’t present as a clean short. The trick is applying them thoughtfully, and designing the control system so normal machine behavior doesn’t look like arcing fault behavior.

Best practices from a controls engineer’s perspective, the stuff that actually prevents arc faults:

Use proper torque. Not “tight.” Torque. The number matters. I’ve watched apprentices learn this the hard way when a “tight” terminal loosened after a week of heat cycling.

Use ferrules on fine-stranded conductors going into clamp terminals. This one change eliminates a lot of loose-strand nonsense and improves connection stability.

Route wires like you care. Protect against abrasion. Add grommets and bushings. Use listed fittings. Don’t run conductors across sharp sheet metal because you’re in a hurry.

Separate noisy power wiring from sensitive control wiring. It’s not arc-fault prevention directly, but it reduces weird waveform noise and troubleshooting confusion. And it makes the system behave.

Inspect for heat. Thermal scans during PM on loaded equipment catch loose terminations before they become a fire. Discoloration is your friend. Smell is your friend too. If you smell hot phenolic, don’t ignore it.

And for the love of clean work, stop stacking conductors under terminals that aren’t listed for it. That’s how you get intermittent contact and series arcing. If you need a distribution block, use a distribution block.

Bottom Line Benefits – Why Bother With All This Protection

Arc-fault protection isn’t about being fancy. It’s about not waking up to sirens. It’s about not losing a plant line because a loose lug decided today was the day.

In homes, AFCIs and good wiring practices reduce the risk of electrical fires from damaged wiring, frayed cords, loose connections, and all the normal dumb stuff that happens in normal life. In many cases, it’s also about code compliance NEC 210.12 is not a suggestion, and inspectors don’t care that your cousin “never used those.”

In industrial settings, the benefits are measured in prevented downtime, avoided cabinet fires, and fewer “mystery” heat issues that chew up components. Insurance folks like documented maintenance. Safety folks like fewer ignition sources. You like not being the person who has to explain scorch marks to management.

And honestly? Once you’ve seen what a tiny arc can do inside a wall cavity or a control cabinet, you stop arguing about whether protection is “worth it.” You start asking where it makes sense and how to apply it without creating a troubleshooting circus.

Wire a GFCI Outlet – 2026 NEC GuideNFPA 70E Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace (official NFPA site)FAQ about ARC Faults

What actually is an arc fault?

An arc fault is unintentional arcing—current jumping across a gap or tracking across a damaged surface—creating localized high heat. It can be a series arc (loose connection in series with the load) or a parallel arc (between conductors or to ground). It’s a common ignition source for electrical fires because it can persist without tripping a standard breaker.

What’s AFCI protection anyway?

AFCI protection is arc-fault protection provided by an arc fault circuit interrupter device—usually a breaker—that monitors current waveforms and trips when it detects patterns consistent with dangerous arcing. It’s designed around standards like UL 1699 and is meant to reduce fire risk, not to replace good wiring practices.

What makes AFCI breakers trip?

Real arc faults, for one loose connections, damaged wiring, frayed cords. They can also trip from miswiring (shared neutrals done wrong, loose neutrals in the panel), or from certain loads that generate electrical noise signatures. If it trips repeatedly, treat it like a legitimate problem until proven otherwise. Bypassing it is how you end up with a “mystery” fire.

Arc fault vs ground fault – what’s the difference?

Ground fault is current leaking to ground, often a shock hazard. GFCI devices trip on imbalance between hot and neutral. Arc fault is unintentional arcing that creates heat and fire risk; AFCIs trip based on waveform patterns. You can have both at once, but they’re not the same thing. One protects people from shock primarily; the other targets fire risk.

Should every circuit have arc fault protection?

In dwelling units, code drives a lot of it, and the trend has been broader AFCI coverage. In industrial and commercial, it depends on the circuit type, the equipment, and what’s permitted and practical. I’m a fan of protecting circuits that feed receptacles and general-purpose outlets in areas where cords get abused. For dedicated industrial loads, it’s more nuanced—sometimes other protective schemes make more sense. “Every circuit” is a nice slogan, not a design standard.

Why the hell does my AFCI keep nuisance tripping?

Usually it’s wiring or a particular load. Start by unplugging everything and seeing if it holds. If it still trips, check terminations—especially neutrals and look for damaged wiring. If it only trips with one device, that device (or its cord) may be failing or just noisy. LED drivers, treadmills, cheap power supplies, and brushed motors are repeat offenders. In control panels, coil chatter and unstable control voltage can mimic arcing behavior.

Can AFCI double as GFCI?

Not by itself. A standard AFCI breaker is not a GFCI. But dual-function AFCI/GFCI breakers exist and are commonly used where both protections are required. Read the labeling and make sure it’s listed for the panel and the application.

Cheapest reliable brand?

If you’re shopping purely by cheapest, you’re already walking toward pain. Stick with reputable manufacturers Leviton, Siemens, Eaton, Schneider Electric and buy through legitimate supply channels. The most expensive breaker is the counterfeit one that fails, or the cheap one that creates endless call-backs. Also: match the breaker to the panel listing. Mixing brands because “it fits” is how you end up with a device that isn’t listed for that panel.

Any industrial alternatives to AFCI?

In industrial environments, you often lean on layered strategies: proper overcurrent protection, good enclosure design, thermal monitoring, insulation resistance testing, vibration control, correct wiring methods, and disciplined maintenance. For certain circuits (like 120 V receptacle circuits in a plant), AFCI can still be a solid layer. For other circuits, AFCI may be impractical due to load signatures or system design. The alternative is not “do nothing.” The alternative is designing and maintaining like you expect the machine to live a hard life.

What if my old panel can’t take AFCIs?

Sometimes older panels don’t have compatible listed AFCI breakers available, or the neutral/ground bar setup makes retrofits messy. Don’t force it with unlisted combinations. Options can include panel replacement, adding properly listed protective devices upstream where permitted, or redesigning circuits. This is where you bring in a qualified electrician who understands listings, code, and the real-world tradeoffs.

Do AFCIs prevent all electrical fires?

No. They reduce risk from certain types of arcing faults. You can still have fires from overloaded circuits, failing appliances, bad heaters, poor ventilation, or plain old negligence. AFCIs are one tool. A good one. Not a miracle.